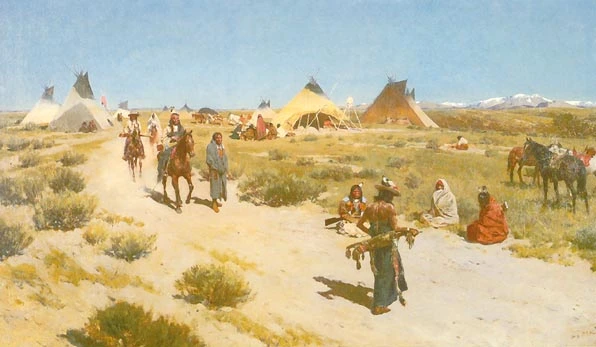

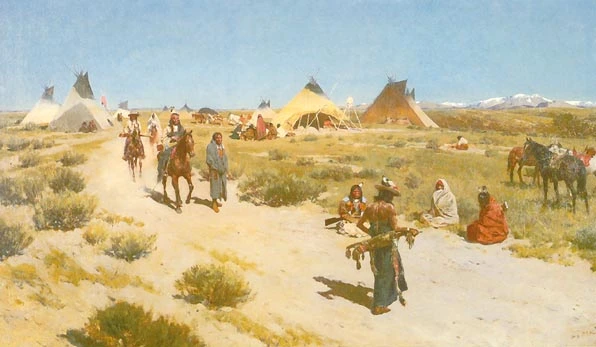

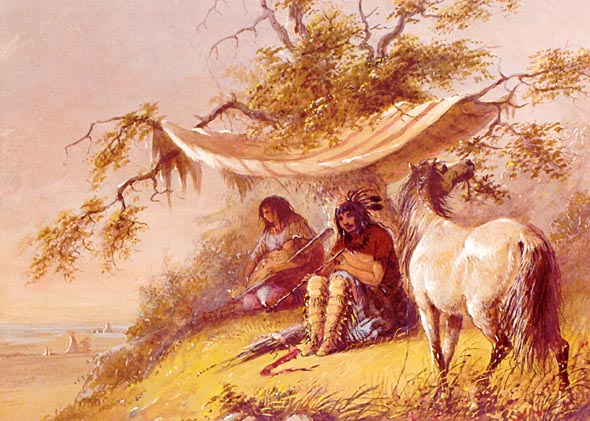

“Indian Camp” by Henry Farny, Cincinnati Art Museum

The plight of the Arapahos is echoed through the many Indian tribes across this vast continent. When the whites first began their westward expansion their numbers were not threatening to the Indians but as the volumn grew, a domino effect eventually forced the Arapaho in the late 1700s from their territory along the Red River in northern Minnesota to the central plains.

“Permit us to dwell for a long time on these beautiful prairie lands.”

When Chief Medicine Man expressed this hope to government officials in the 1850s, the Arapaho still followed traditional ways, camping along the foothills in the winter, roaming the plains to hunt buffalo in the spring. But each year, more and more immigrants, explorers and soldiers were coming to the plains, and Medicine Man saw their coming as a sign of danger to the Arapaho land.

That land covered a vast section of the central plains, from the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains across today’s eastern Colorado, western Kansas, southern Wyoming and a strip of southern Nebraska. Known as the land between the two rivers (the Platte and Arkansas), it stretched towards the mountains like a great, dried seabed, parched in the summer sun and buried in the winter by snow.

By the 1830s, they found themselves sharing this land with the Cheyenne, who had come south to trade at Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River and, after encountering the large buffalo herds, decided to stay. The Arapaho did not resent Cheyenne in the area. In fact, as the “businessmen of the plains,” they probably welcomed the opportunity to trade with Cheyenne villages. At any rate, the two tribes staked out different locations, with the Cheyenne camping on the plains and the Arapaho living in the foothills of the front range. They especially liked the Estes Park area and the North and South Parks where buffalo was plentiful. Although Lakota and Pawnee hunting parties made frequent trips to the central plains, other tribes, as well as a few white traders traipsing through the area, recognized that the land between the two rivers belonged to the Arapaho and Cheyenne.

With the exception of those few traders, including William and Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain who established Bent’s Fort in 1833, the Indians had the central plains to themselves. Whites did not begin arriving in large numbers until 1848 when 1,000 immigrants on their way to the northwest headed down the Oregon Trail which ran south of the Platte River. Within the next few years, thousands of Mormons followed Brigham Young into Utah along the Mormon Trail north of the Platte. Colonel John C. Fremont led exploration parties up and down the plains, and the Army of the West, under Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny, marched down the Santa Fe Trail to the Mexican War.

By 1849, the steady stream of whites turned into a deluge as 50,000 goldseekers, bound for the California gold rush, crossed the plains…more goldseekers than the entire population of Plains Indians, which was then estimated at 40,000.

Like the immigrants, explorers and soldiers before, the goldseekers trampled the wild grass, killed the buffalo, wasting most of the meat and skins, and dispersed the large herds. Thomas Fitzpatrick, the first government to the Arapahos, Cheyennes and Lakota, complained to Washington that “the immense emigration traveling through Indian country for the past two years has desolated and impoverished it to an enormous extent.”

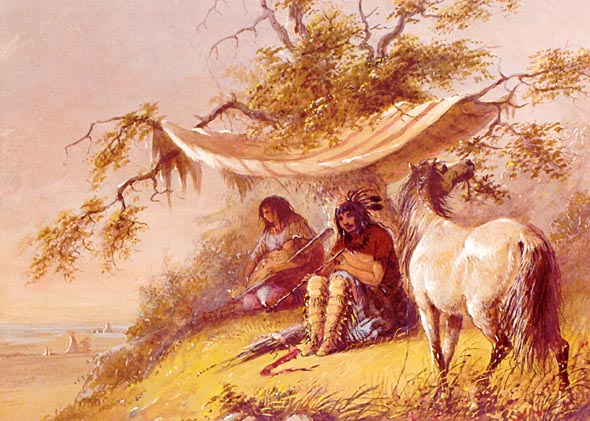

“Arapahos” by Alfred Jacob Miller, Courtesy of Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore

Conflicts were inevitable between the white new-comers and the Indians who saw both their land and buffalo in danger. In an attempt to head off serious problems, the government called a treaty council with the Plains Indians at Fort Laramie in late summer, 1851. Judging by the number of Indians who came to the council – 10,000 Arapahos, Cheyennes, Sioux, Assiniboines, Arikara, Gros Ventres, Crows and Shoshoni – they were anxious as the government to reach an agreement on the rights and obligations of different peoples on the plains.

Before the council could get underway, however, thousands of Indian ponies had eaten their way through the grasslands near the fort, causing Commissioner D.D. Mitchell to move the council site to Horse Creek, thirty-seven miles away. On September 15, following three weeks of meetings, the leading men of the plains tribes signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie, the first treaty between the Plains Indians and the United States government; the most important document in the history of Indian-white relations on the plains.

In the treaty, the government acknowleged Indian ownership of the plains, even specifying which land belonged to each tribe. Expressing the optimistic note the council ended, Father De Smet wrote: “In future, peaceable citizens may cross the desert unmolested, and the Indian will have little to dread from the bad white man, for justice will be rendered to him.”

Despite such optimism, whites continued to slaughter the buffalo, destroy the grassland, and introduce diseases such as smallpox, cholera, and whooping cough that devastated the tribes. Treaties came and went; the whites came and came and the Indians simply went. For years the Northern Arapaho wandered the plains; a people without a country. By 1876, with the land gone to whites and no reservation to settle on, the Northern Arapaho again met with government officials. By this time, the government no longer regarded the tribes as nations with whom treaties had to be made. Instead, an “agreement” was reached in which the Northern Arapahos, Cheyennes, and Sioux waived all claim to any lands and promised to settle on reservations set out by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

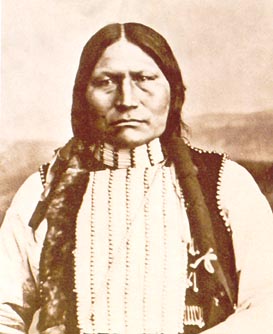

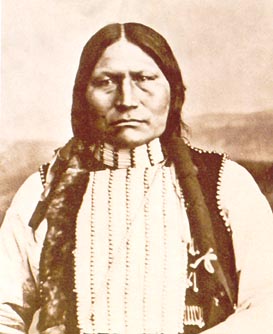

Again, the Northern Arapaho Chiefs Black Coal, Little Wolf, and Sharp Nose signed the agreement, not wanting to forfeit rations their people needed to stay alive. But instead of going to the reservations, they kept pressing the government for a separate reservation in Wyoming. Finally, after Northern Arapaho warriors worked as scouts in 1876 and 1877, the government allowed the tribe to remain in Wyoming Territory.

Based on government promises, the tribe hoped to move to the Powder River Country on their own reservation. Instead, they were settled “temporarily” on the Shoshoni reservation in 1878. Eight years later, government agent Sanderson Martin informed them the government had no intention of forming a separate reservation near the Powder River. The Northern Arapaho were on the Shoshoni reservation to stay.

In those eight years, the tribe settled in two large camps, ten miles apart, along the Little Wind River, whilst a third group, under Chief Black Coal, lived near the forks of the Popo Agie and Wind River close to the St. Stephens Indian Mission. On this new land, they worked to establish the farms and ranches that can still be seen today.

Not until 1927, when the government paid four and a half million dollars to the Shoshoni tribe for reservation land given to the Northern Arapaho, could the Northern Arapaho people feel secure that this new and beautiful land at the base of the Wind River Mountains was finally home.

Northern Arapaho Chief Black Coal

Chief Black Coal’s Camp